Robin Hill: Lang & O’Hara Gallery

March 14 - April 13, 1991

Lang & O’Hara Gallery

New York, NY

exhibition catalog

1991 Robin Hill, The New Yorker

1991 Robin Hill, New York Magazine

1991 Robin Hill, Arts Magazine

1991 Robin Hill, ARTnews

catalog essay by Theresa Pappas:

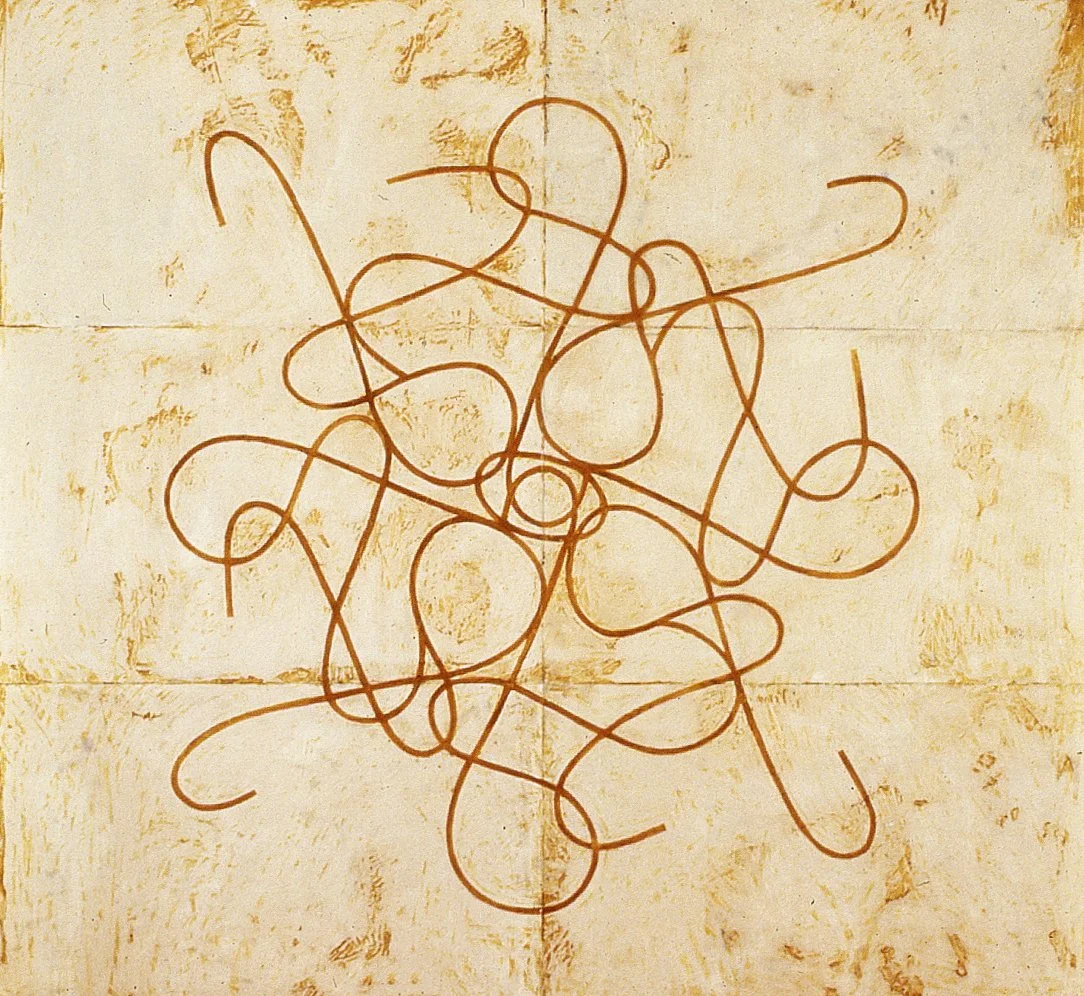

Robin Hill is a collector of odd, eccentric objects-the discarded, the fragmentary. She picks up things from curbside trash piles and from beaches. She takes them home and she keeps them in sight: a largerthan-life steel turnbuckle; a mysterious upholstery grid woven of wire and string; toy trucks hammered from tin cans; rocks; film negatives. Though these things do not themselves become part of her sculptures, her attitude towards them is an essential aspect of her creative process. When she can't take the actual items with her, she still collects their images: chunks of glacial ice washed up on the Alaskan coast; Chinese porcelain vases in a case at the Metropolitan Museum; the shifting configurations of silos, sheds, and outbuildings seen from a moving train. Her appreciation of the unexpected find guides the way she works and resonates within her sculptures.

In her earlier pieces, made of melted parrafin cast over and subtly exposing skeletons of wood and cardboard, the heavy, dignified columns evoked a half-forgotten mythology. suggesting structures unearthed and reassembled from an ancient civilization, an industrial wasteland, or perhaps---with the hints of medical cross-sections or diagrams-from the body itself. In the next stage, Hill literally pulled a shape upwards from a spiral drawing on plywood, and instead of casting wax she troweled it over the rigid armature. The architectural / archaeological elements became more figurative, suggesting caryatids, fertility goddesses, Cycladic figurines, fragments of draped clothing, glimpses of body parts usually hidden.

The sculptor Noguchi said: "You can find out how to do something and do it or do something and then find out what you did. I seem to be of the second disposition. I 1ust do it and then maybe I try to name it or find out what I did."' Hill shares this disposition. Noguchi's words, recorded in her notebook, remind her to embrace the unpremeditated features of her work, to value the possibility of "finding" a piece perhaps only when she has completed it. Hill has written: "I oen think a crystal ball would be useful-maybe I could speed up the process, avoid mistakes, if I knew where I was headed. I find, however, that the past does add up to a kind of retro-crystal ball. By looking backwards I am able to see the continuity of my visual undertakings, and to appreciate the idea of blind faith. that there will be the same continuity in future undertakings." Retracing her steps, Hill sees the progression of her work as a Journey that has begun to circle back to its beginnings. Despite the obvious differences in her work from its earliest to its most recent stages. she feels she has returned to a like sensibility, "reconnecting with a kind of purity" that was obscured as her pieces became more complex.

In the new work, she creates small clay models to generate images, which frees her from the constraints of other materials. (Hill does make drawings as well. but these have never been plans for sculptures: they're parallel explorations in their own right.) The enlarged models, built from wood, wire mesh and concrete, now become molds for· the skins, or shells, that she applies, removes, reassembles, and then treats in various ways. To the positive solids which previously constituted the final piece-to be treated with wax-she has applied and released yet another layer, fiberglass in three of the pieces, rubber and wax in the others. She compares this process to hatmaking. in which a solid wood form is used to mold another softer material (felt, cloth, leather). "So I've gotten these skins, free of armature, truly translucent and light." Her new methods have brought forth pieces that suggest an even closer-sometimes uncomfortably closeexamination of the topography of the body, with forms that allude to internal organs. orifices, sexual devices, dissections. These are images that have emerged from an interior world as intimate and as foreign as our own beating hearts.

Valve. in both its title and its shape, refers explicitly to the heart. probably a manufactured one. Hill's treatment of the two circular openings with beeswax-saturated cotton upholstery cord result in highly defined edges. Like the rims of condoms or balloons, these openings suggest that the entire piece might have been unrolled or inflated. This manufactured quality becomes even more evident in the outdoor installation. Replacement Valves, which replicates the same form four times. Arraying the parts in different positions, Hill disguises their uniformity and makes a puzzle of their connections to each other. The title Ro-Cham-Beau refers to the childhood game also known as Scissors-Paper-Rock, and, like the game, its three components explore relationships among different materials. suggesting hierarchies of dominance and vulnerability. The same form takes on different properties. different identities: an ample torso-like shape resting on the floor: a fragile shell of that torso levitating a few inches off the ground: a rubbery casing collapsed into itself. In Chaperone. Hill reproduces parts of the central form. placing them around it like a shedding skin, or like smaller offspring escorted by a mother figure.

In the landscape of Hill's work, the pieces seem displaced. Separated from their implied settings, however, the forms are even more dramatically themselves-whole and distinct. The work may be described as peaceful, but this is an active-even aggressive-calm that accummulates energy, like the powerful interior focus of prayer or meditation. The translucent sculptures pulse within their skins, as if ready to stretch them taut or slough them off. They sit on the floor, seeming to sink under their own weight or to float upwards. These pieces are still and concentrated while they also imply a desire to be other than what they are at this particular moment, pushing at their seams, expanding into other dimensions. Hill has spoken of her admiration for the photographs of Cartier-Bresson, and she likes to think of her pieces as "gestures or postures frozen in time." The displaced quality not only sets the pieces apart: it also calls for their location within a temporal context, the pieces themselves seemingly aware of both past and future, the continuous unfolding of events and actions: states of being dissolving into each other: tides of breath and light. tumescence and decay.

Hill's carefully "discovered" creations reclaim for us the buried. the abandoned, the unacknowledged. Her sculptures embody gestures and longings that are surprising and familiar at the same time. Walking among the forms that Hill has arranged to wash up at our feet, we may find ourselves thrilled with recognition and perhaps slightly uneasy about our connection to these objects. Her sculpture compels us to see the life unfolding inside things and reveals the underlying structure of the things in our lives.