Robin Hill’s Art of Processes

by Raphael Rubinstein

A conceptually ideal approach to writing about Robin Hill’s work would consist of taking some pre-existing text, preferably discovered by chance, and subjecting it to a number of transformative procedures. For instance, one could start with these words found in a statement by the artist: “My work assumes many forms. Underlying all of these forms is a response to matter and phenomena in my immediate vicinity” (see catalogue for “Proximity,” The Work Space, New York, 2002). Imagine, if you will, these phrases repeated so that they filled this whole page, or even an entire book. Now imagine them shrunk to so small a size that the line of type looked like a stray hair on a page and could only be read with a powerful magnifying glass. Or suppose each term was replaced with its dictionary definition, enlarging the statement tenfold. The text could also be overprinted with other sentences, creating a kind of palimpsest, or turned around to read backwards: “Vicinity immediate my in phenomena and matter to response a is forms these of all underlying. Forms many assumes work my.”

Far from being random, these proposed procedures for an experimental commentary on Hill’s work are themselves derived from another text by the artist. In a statement written for her seminal “Blue Lines” exhibition (Lennon, Weinberg Gallery, New York, 1995) Hill described how “the formal principle which dictates the geometric possibilities in both the floor and wall drawings is the manipulation of one singular line formation, chosen at random, through repetition, enlargement, reduction, layering, and inversion.” Visitors to this memorable show encountered large oil-stick drawings of intricately looped blue lines and, on the floor, 4,000 small blue plaster forms cast from paper cups. As Hill’s description suggests, the plaster forms were arranged to echo the mandala-like configurations of the drawings, though at an even larger scale. As she says, she manipulated a linear motif by, in succession, repeating it, enlarging it, shrinking it, superimposing it and flipping it around.

From the beginning of her career, but more emphatically over the last decade, Hill has been an artist whose work is driven, in large part, by an insatiable curiosity about what happens to forms and materials when they are subjected to various procedures (as in the morphing loops of “Blue Lines”). For this reason Hill is often seen as continuing the legacy of process art, and, indeed, she does owe a debt, openly acknowledged by the artist, to predecessors such as Eva Hesse. But there are also many points at which Hill’s work diverges from much process-oriented art of the 1960s and 1970s. Perhaps the most important of these is Hill’s emphasis on using a multiplicity of techniques and procedures. She is never content to simply apply one process to one material or to one form. Instead, she brings to bear as many of them as her imagination or an exhibition space can accommodate. What Hill makes is not so much process art as it is an art of processes.

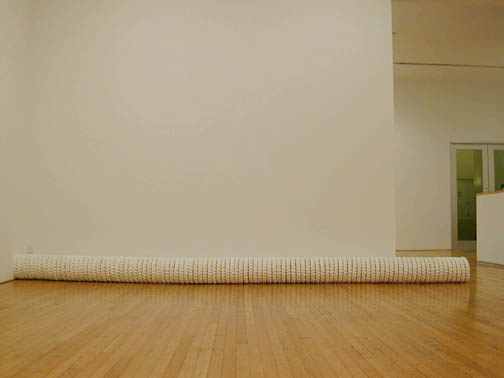

The present exhibition offers striking examples of this fundamental feature of her practice. Look, for instance, at a pair of sculptural works, Against the Wall and Concretion, both created in 2004 and envisioned to be shown in tandem. Against the Wall consists of 100 circular elements affixed to the wall in a tight 110-by-110-inch grid. Each element is a 10-inch-diameter plywood disc onto which Hill attached some 120 handmade wax balls arranged in concentric circles. About the size of a jawbreaker candy, these balls, which are noticeably irregular, are held in place by more wax that has been poured into the interstices. As an ensemble, the work combines dense geometric patterning with a rich tactility. Structured around ever-smaller circles—the wood discs, the rings of wax balls, the wax balls themselves—Against the Wall has the part-to-whole dynamic of a mosaic. Its companion, Concretion, consists of 100 Hydrocal discs cast from the wood-and-wax discs of Against the Wall, but instead of being displayed as a wall relief, these lumpy white objects are pressed together on the floor to create a 182-inch-long tubular shape that suggests a core sample drilled from ground, a toppled column or a rolled-up carpet. As with “Blue Lines,” Hill here presents two versions of the same motif, using two different techniques and using two different strategies of presentation. Another significant difference, one that viewers might not immediately appreciate, is the enormous discrepancy of time that the two pieces required: certainly there was a lot of work involved in casting the 100 units of Concretion, but even that represents a fraction of the labor required to make the roughly 9,000 wax balls of Against the Wall. (Although never actually visible, a sense of epic labor accompanies many of Hill’s sculptures, hovering at the margins as part of their conceptual content.)

What are the implications of this approach? One, of course, is to stress the interrelatedness of various artistic mediums. Hill’s frequent passage from drawing to sculpture to photography (in her cyanotypes) and from wall-hung to freestanding works, is a challenge to the stubborn academic and institutional tendency to segregate works by medium and artists by type (painter, sculptor etc.). On a larger scale, one of the things it invites us to consider is how everything that happens in the world, everything that has ever happened, is simply the rearrangement of matter: X number of molecules or atoms moved by some force from point A to point B. Therefore, a work of art is, at the most basic level, the result of material being transferred from one location to another: in the making of a painting, for example, paint is moved from tube to palette to canvas, or simply from can to canvas (trying, as Frank Stella one remarked, to keep the paint looking as good as it did in the can). Generally this movement of matter is taken for granted, but in Hill’s work it often takes center stage, with illuminating results.

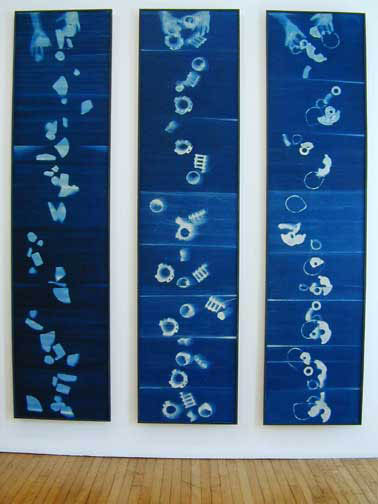

If Hill’s multiple transformations (significantly, she titled her most recent New York show, in which much of the present work debuted, “Multiplying the Variations”), her carrying of forms from one medium or material to another, signals interrelatedness, so, too, does another important aspect of her practice: the use of objects—often found, sometimes salvaged, on other occasions bought—that were originally produced for some other purpose.[i] She came across the plywood discs of Against the Wall, for instance, in a manufacturing surplus store in Berkeley (in a coincidence the artist notes, these were the identical size of the discs she fabricated for a 1997 piece, add lint. re-coil. the rolls are now ready to serve. Other works in this show are made from cotton batting gathered at a factory in Brooklyn that manufactures shoulder pads (Accumulation), thousands of small discs of mica discovered in a dumpster (Mica and Pins) and rusted stove parts that Hill found washed up on a beach in Nova Scotia (Beach Debris). This rusty flotsam is presented twice, displayed on a sand-covered table and in a series of cyanotypes (a photogram-like process popular in the 19th century that Hill frequently employs). Her most recent work, the sculpture-photography-sound installation Kardex (2006), made in conjunction with composer Sam Nichols, uses a steel, visual storage, filing cabinet designed by James Rand Jr. for the American Kardex Company in 1915 for business use and no doubt a boon to information storage in the pre-computer era. This installation features walls of institutional green and sturdy utilitarian furniture typical of a 1950s back office. Hill clearly has a fondness for outmoded technologies; as she eloquently puts it, many of the things she works with have come to her “on the tide of a much greater obsolescence. . . the shift from 19th century industrial processes to the digital, the virtual, and the outsourced.”

In each of these cases, the materials become ambassadors between the function- and profit-driven realms of industry and commerce (albeit those of yesteryear) and the less pragmatic world of art. Interestingly, when Hill uses such materials they almost never announce themselves as “industrial” or “found” (Beach Debris, where it’s pretty clear we are looking at pieces of some functional device, is, like Kardex, an exception), which is in contrast to how industrial cast-offs are generally employed by artists. This seems to be largely the result of Hill’s visual sensibility: in her scavenging she is attracted to items that aren’t obviously functional, things that, when used in manufacturing, tend to end up concealed inside other materials or are discarded as remnants or byproducts. In Accumulation, for instance, it’s unlikely that many viewers would be able to guess at the origin of these small discs of spongy cotton that Hill has made into 15 square sheets that move from the wall to the floor. Even more mosaic-like than Against the Wall, Accumulation surprisingly relies on friction alone to hold together the cotton elements (behind them is a sheet of paper with more cotton attached). In a recent in-depth interview with the painter Ron Janowich, Hill discusses the genesis of Accumulation, revealing how when she began to work with this material she wasn’t at all sure what form it would take (early configurations included a curving line and a tree form). Her eventual discovery is a nuanced, haptic structure that builds on such precedents as Piero Manzoni’s monochromes and wall-to-floor paintings by Ellsworth Kelly and others. Equally important in establishing interrelatedness is the way Hill incorporates those components she makes herself with the found elements: hers is a hybrid art in its seamless joining of the found and the handmade.

There is also interrelatedness to be seen in the modularity that runs through the work. The basis of this modularity is the unremarkable appearance of the individual parts. In her interview with Janowich she recalls how in “Blue Lines” “the idea with the cups was that each unit on its own was nothing. They became essential through their contribution to the whole.” This nothingness of the units acquires further meaning in Mica and Pins, a wall piece that Hill speaks of as a drawing. Once again the result of an intriguing dumpster find—countless tiny mica washers strung onto a long string—the work appears as sets of looping, interwoven diaphanous lines. In fact, it consists of thousands of closely spaced straight pins (placed according to a template) with a single mica washer hanging on each one. Looking something like miniature CDs, the semi-translucent washers reflect light but because of their innate irregularities and the different angles at which they come to rest on the pins, the lines they create are full of tonal nuance. The ghostly shadows cast by the washers and pins add to the immaterial qualities of this unconventional wall drawing. Another feature of Mica and Pins, perhaps not immediately evident, is how the quadrilateral drawings are constructed from single motifs submitted to Hill’s favored techniques of repetition and inversion.

Another technique that runs through Hill’s oeuvre is chance. Obviously, her reliance on whatever materials happen to be strewn in her path, her constant attention to her “immediate vicinity,” means that accident plays a central role in the genesis of each piece. If she hadn’t come across that string of mica washers, if she hadn’t had a studio near a shoulder pad factory, if she hadn’t come across a cache of plywood discs, the works using these materials would never have come into existence. But this doesn’t mean that Hill is a mere slave to serendipity: when she looks into a dumpster, visits a factory or wanders the aisles of an industrial supply store, the materials that attract her tend to be those that respond to her well-defined sensibility. Chance or accident is never the determining factor in her work, it is simply another of her chosen processes.

On occasion, chance takes on a prominent role not at the moment the material is found but during the actual making of the piece. In The Shape of Things to Come, for instance, Hill determined the forms of dozens of small planar wax sculptures by dropping lengths of string into curvilinear designs. Looking back to chance-determined works by Duchamp and Arp, this work also evokes mid-century abstract sculptures and (to my eye) cartoon figures. These five-inch-high wax-and-string biomorphs are set on wax pedestals cast from plastic cups. Hill makes no attempt to hide the modest origin of these pedestals, something that is in keeping with her overall lack of pretension and taste for humble materials. To some degree, she sees her function as bringing attention to the beauty and artistic potential of quotidian stuff. In this mode, she has made aesthetically riveting works with such seemingly unpromising materials as orange peels (Bushwick Wheel, 1998) and plastic bags (One Hundred Feet of the Sweet Every Day, 2001). One of her most inventive (and perhaps a bit mad) exercises in the poetics of the everyday was a 1997 piece that involved unspooling 100 rolls of Scotch tape, adding cotton batting to their adhesive surfaces and rolling them up again. The work’s recipe-style title (add lint. re-coil. the rolls are now ready to serve) underlines the demystifying impulse in Hill’s work.

But if her always graceful art revels in accessible materials and easily explained processes, it also is marked by repetitive, labor-intensive methods that approach the trance-inducing practices of countless mystical orders around the world. Just as a religious seeker might take a single phrase or physical movement and, through disciplined repetition, transform it into a vehicle of revelation, so does Hill pursue illumination through her meditative making. If her work stands at the intersection of several vectors of modern art practice (found-object sculpture, process art, chance procedures, monochrome art, endurance-based performance), it also is located at the crossroads of the mundane and the mystical, where the physical object pulls us into invisible realms.

(Unless otherwise noted, all quotations taken from Ron Janowich’s interview with Robin Hill conducted for the upcoming “Cultural Recycling” issue of the journal Other Voices; an audio version can found on Hill’s web site: www.robin-hill.net)

[i] . Hill took the title “Multiplying the Variations” from Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. The phrase occurs in the book’s final chapter, The Phenomenology of Roundness, which could have been an effective title for the show.

Robin Hill: Multiplying the Variations

September 23 - October 23, 2004

Lennon, Weinberg, Inc.

514 West 25 Street

New York, NY 10001

September 7 – October 5, 2006

California State University, Stanislaus University Art Gallery

801 West Monte Vista

Turlock, CA 95382

Robin Hill’s Art of Processes

by Raphael Rubinstein

exhibition catalog

artcritical

Robin Hill: Multiplying the Variations

by David Olivant